Second Journey: Afghanistan

Frequently in the headlines in Europe for unfortunate reasons (the Taliban, civil war, etc.), Afghanistan is a country we may think we know well. But in the end—who are the Afghans? Let’s go and find out.

6/18/2025

Bagh-e Babur, or the Gardens of Babur, in southeastern Kabul

Compared to Abkhazia, textual resources on Afghanistan are abundant. Just take a look at the holdings of the Centre d’Études et de Recherches Documentaires sur l’Afghanistan (CEREDAF, Center for Documentary Studies and Research on Afghanistan) to be convinced—their bibliography spans over a hundred pages. The task, then, is to identify the most relevant books on the subject.

History, Sociology, Culture

So, first of all: who lives in Afghanistan? The question is worth asking, since Afghanistan itself has, apparently, never conducted a precise census of its population. Nevertheless, Wikipedia comes to the rescue with the following estimated proportions of ethnic groups within the Afghan population:

Pashtuns (42%)

Tajiks (27%)

Hazaras (9%)

Uzbeks (9%)

Aimaqs (4%)

Turkmens (3%)

Baloch (<2%)

Pashayi or Nuristanis, Arabs, Kyrgyz, Indian communities, etc.

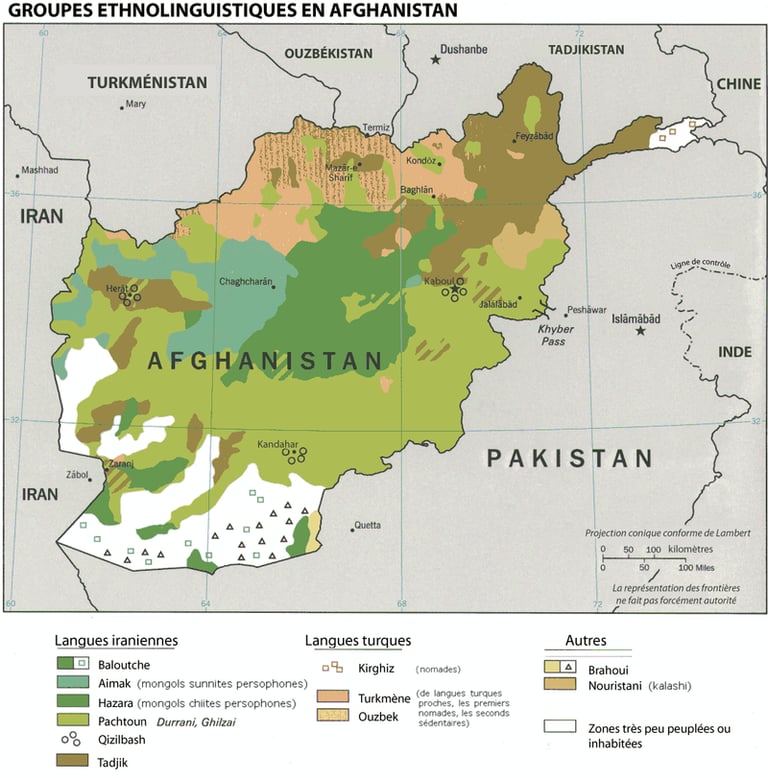

Here is a geographical distribution of these ethnolinguistic groups (the map come from Wikipedia, I can't translate it) :

My goal is therefore to find books related to at least the main groups, from which I’m excluding the Tajiks, Uzbeks, and Turkmens, for the simple reason that I expect to find more accessible resources on them once I reach Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan.

To get a proper introduction and a clearer overview, I chose Si l’Afghanistan m’était conté (If Afghanistan Was Told to Me) by Alain Coppolani, which promises insights into Afghanistan’s history, culture, and society. I’m pairing this with Paysages naturels, paysages culturels du centre de l’Afghanistan. Hindou-Kouch, Lacs de Band-e Amir, Vallée de Bâmiyân (Natural landscapes, cultural landscapes of central Afghanistan. Hindu Kush, Band-e Amir Lakes, Bamiyan Valley), published by the aforementioned CEREDAF. According to the information I’ve found, this book has the advantage of certainly addressing Hazara culture.

For the Pashtuns, I turned to Les Pachtouns, un grand peuple sans pays (The Pashtuns, a great nation without a country) by Alain Lamballe. To this, I’m adding Les Gardiens des Monts Pakistanais, les Pathan (Guardians of the North-West Frontier) by André Singer. It appears that “Pathan” is simply an alternative spelling of “Pashtuns” or “Pachtounes”—something I’ll confirm through reading.

To conclude the “history, sociology, etc.” section, I’ll be reading Les Talibans face à l’opium (Talibans Facing Opium) by Héloïse Dross. This choice isn’t motivated solely by my interest in the organization of drug production. The opium economy supports around two million people in Afghanistan and accounted for 35% of the country's GDP in 2005, which certainly justifies attention—it’s not some marginal activity. I’m especially curious about how the Taliban approach the issue, as it provides a lens through which to understand who they are, the structure of their worldview, and how they manage the contradiction between their values and the practical need to continue cultivating opium.

Literature

Beyond the language barrier, the political context does not lend itself to the discovery of Afghan literature. Generally speaking, the country has endured decades of war, and its people naturally have other concerns than literary production.

A large portion of Afghan literature appears to be poetry, a literary genre already challenging to translate in its own right. History has only compounded that challenge. Afghanistan, being a traditionally Muslim country, clashed with the Saur Revolution of 1978, which was Marxist-Leninist in orientation and thus anti-religious. This period lasted about twelve years.

At the other extreme, the country fell under Taliban control from 1996 to 2001 and again since 2021. Considering that they burned 55,000 rare books and destroyed several libraries, it’s fair to assume that they aren’t exactly promoting Afghan cultural exports. Moreover, it seems to me that women play a central role in contemporary Afghan poetry, but given the current state of their rights, it feels sadly unrealistic to hope to read their work someday. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to find any of their texts. If you have leads, don’t hesitate to contact me.

Here are the books I’ve chosen:

Les figues rouges de Mazâr (Red Figs of Mazar) by Mohammad Hossein Mohammadi, a short story collection.

La plaine de Caïn (The Plain of Cain) by Spôjmaï Zariâb. Though born in Kabul in 1949, Spôjmaï Zariâb has lived in France since 1991, which makes her work more readily accessible.

Légendes et coutumes afghanes (Afghan legends and customs) by Ria Hackin and Ahmad Ali Kohzad. This book is the result of a collaboration between French archaeologist Ria Hackin and Ahmad Ali Kohzad, a member of the Afghan Academy and curator at the Kabul Museum. Published in 1953 and never reissued since.